|

|

|

|

| Digestive

System Navigation links

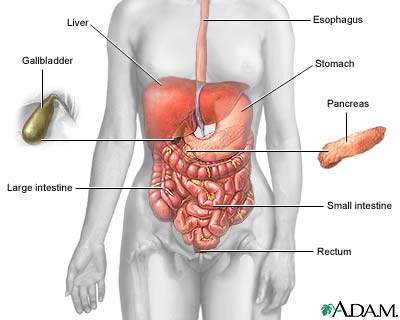

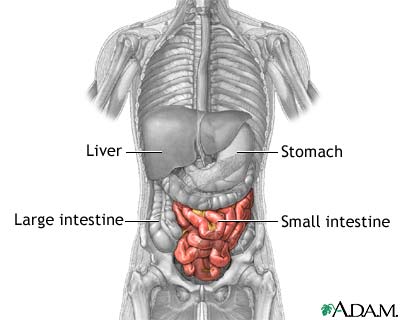

Nutrition permits us to take in and use food substances that the body converts to energy and body structure. The digestive system includes all the organs and glands involved in this process of eating and digesting. Starting in the mouth, a long muscular tube provides continual fluid and vital nutrients. The coiled intestines alone are about 24 feet long. After we consume food, the body mechanically and chemically breaks it down, then transports it for absorption and defecation (final waste removal). The digestive glands (salivary glands, pancreas, liver, and gallbladder) produce or store secretions that the body carries to the digestive tract in ducts and breaks down chemically.

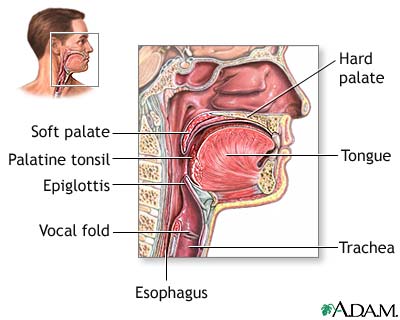

Food processing begins with ingestion (eating). The teeth aid in mechanical digestion by masticating (chewing) food. Mastication permits easier deglutition (swallowing) and faster chemical breakdown in the digestive tract. During mastication, salivary glands secrete saliva to soften the food into a bolus (semi-solid lump). Saliva contains the salivary amylase enzyme, which digests carbohydrates (starches), and mucus (a thick liquid), which softens food into a bolus. Ingestion starts both chemical and mechanical digestion.

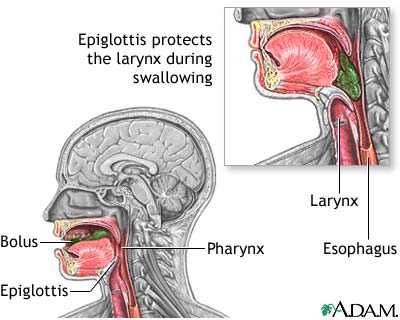

In deglutition, the tongue pushes the bolus toward the pharynx (throat) and into the esophagus, a muscular tube that leads from the throat to the stomach. To prevent food or liquid from entering the trachea (windpipe), the epiglottis (a small flap of tissue) closes over the opening of the larynx (voice box) during deglutition.

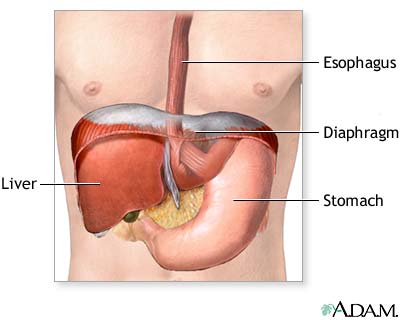

Upon entering the esophagus, peristalsis (wave-like contractions) of smooth muscle carries the bolus toward the stomach. Two layers of smooth muscle, the outer longitudinal (lengthwise) and inner circular, contract rhythmically to squeeze food through the esophagus. Throughout the digestive tract, smooth muscle peristalsis aids in transporting food.

From the esophagus, the bolus passes through a sphincter (muscular ring) into the stomach. All sphincters located in the digestive tract help move the digested material in one direction. When the stomach is empty, the walls are folded into rugae (stomach folds), which allow the stomach to expand as more food fills it. In the stomach, food undergoes chemical and mechanical digestion. Here, peristaltic contractions (mechanical digestion) churn the bolus, which mixes with strong digestive juices that the stomach lining cells secrete (chemical digestion). The stomach walls contain three layers of smooth muscle arranged in longitudinal, circular, and oblique (diagonal) rows. These muscles allow the stomach to squeeze and churn the food during mechanical digestion. Powerful hydrochloric acid in the stomach helps break down the bolus into a liquid called chyme. A thick mucus layer that lines the stomach walls prevents the stomach from digesting itself. When mucus is limited, an ulcer (erosion of tissue) may form. Food is digested in the stomach for several hours. During this time, a stomach enzyme called pepsin breaks down most of the protein in the food. Next, the chyme is slowly transported from the pylorus (end portion of the stomach) through a sphincter and into the small intestine where further digestion and nutrient absorption occurs.

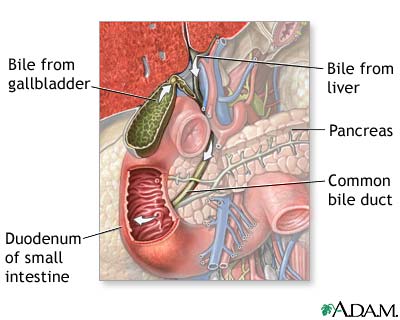

Digestion and absorption: small intestine The small intestine is about 20 feet (6 meters) long and has three parts: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. The duodenum is where most chemical digestion takes place. Here, bile from the gallbladder and enzymes from the pancreas and intestinal walls combine with the chyme to begin the final part of digestion.

Bile liquid is created in the liver and stored in the gallbladder. Bile emulsifies (breaks into small particles) lipids (fats), which aids in the mechanical digestion of fats. The pancreas and gland cells of the small intestine secrete digestive enzymes that chemically break down complex food molecules into simpler ones. These enzymes include trypsin (for protein digestion), amylase (for carbohydrate digestion), and lipase (for lipid digestion). When food passes through the duodenum, digestion is complete.

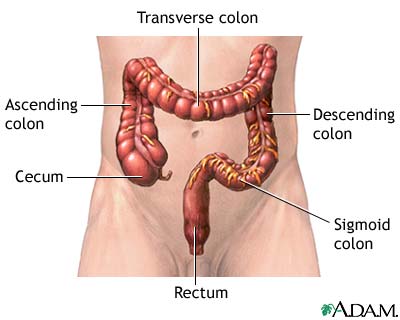

From the duodenum, chyme passes to the jejunum and ileum. Here, tiny villi (finger-like projections) cover the walls of the small intestine. The cells that line the villi are covered with small projections called microvilli (brush border). These projections increase the surface area of the small intestine, allowing the chyme to contact more of the small intestine wall. The increased contact causes more efficient food absorption. During food absorption, food molecules enter the bloodstream through the intestinal walls. Capillaries (microscopic blood vessels) within the villi absorb products of protein and carbohydrate digestion. Lymph vessels (lacteals) within the villi absorb products of fat digestion and eventually lead to the bloodstream. From the small intestine, digested products travel to the liver, one of the body's most versatile organs. Hepatocytes (liver cells) detoxify (filter) blood of harmful substances such as alcohol and ammonia. And, hepatocytes store fat-soluble vitamins and excess substances such as glucose (sugar) for release when the body requires extra energy. Once food has passed through the small intestine, it is mostly undigestible material and water. It enters the colon (large intestine), named for its wide diameter. The large intestine has six parts: the cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum.

The large pouch-shaped cecum marks the beginning of the colon. Attached near the cecum bottom is the vermiform (worm-like) appendix. The appendix contains lymphoid tissue and intercepts pathogenic microorganisms that enter the digestive tract. Sometimes, fecal matter may become trapped in the appendix, resulting in appendicitis (infection and inflammation). The other parts of the colon absorb water and minerals from the undigested food and compact the remaining material into feces. Defecation is the digestive process final stage: feces (undigested waste products) are carried to the rectum through peristalsis and eliminated through the anus. |

Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited. The information provided herein should not be used for diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition and is provided for your general information only.