|

|

|

|

|

Navigation links

The diverse collection of millions of cells and their products that are activated by antigens (foreign substances) make up the immune system. These cells, particularly lymphocytes that have a key role, are in the blood and various organs and tissues throughout the body. Immune reactions destroy, immobilize, or neutralize disease-causing agents, foreign matter, and certain altered body cells such as tumor cells and autoimmune events. When functioning well, the finely tuned immune system mobilizes cells and antibodies appropriate and specific to the antigen challenge.

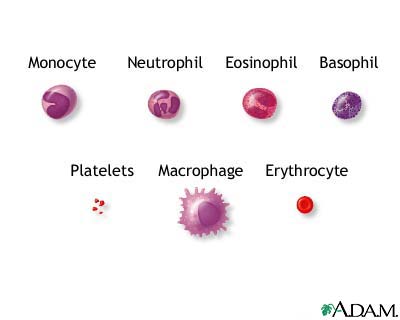

Antigens: nonspecific and specific immunity Antigens originate within the body or from the outside environment. The immune system provides two lines of defense: nonspecific and specific immunity. A first-time encounter with an antigen elicits a nonspecific immune response. Defense mechanisms include skin, mucous membranes, chemicals, specialized cells, and the inflammatory response. Unbroken skin is a formidable physical barrier to most antigens. Mucous membranes line body cavities such as the mouth and stomach. These structures secrete saliva and hydrochloric acid, respectively, chemicals that destroy bacteria. If antigens pass through the defenses, a variety of white blood cells such as macrophages, neutrophils, and mast cells try to destroy them. Other mechanisms in the blood such as complement (antibacterial proteins), interferon (antiviral proteins), and natural killer cells aid in the battle.

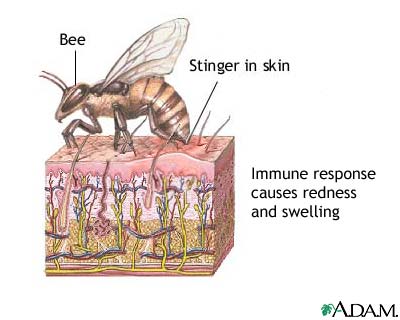

When antigens successfully invade the body through the skin or mucous membranes, their presence elicits the inflammatory response. This response prevents antigen spreading to nearby tissues, disposes of cellular debris from the "battle," and begins damage repair. When the invasion starts, the immune system sends its "soldiers," leukocytes (white blood cells), to battle. Leukocytes such as neutrophils and macrophages ingest and destroy antigens in a process called phagocytosis. If a bee stings you, the presence of the bee venom triggers a nonspecific immune response. White blood cells arrive first on the scene to rid the body of bee venom antigens. As war wages between antigens and white blood cells, battle signs may appear on the affected skin. Inflammation (redness, swelling, heat, and pain) results as the body wards off invaders.

If the body detects an antigen that it previously met, a specific immune response occurs. In this response, the body has been trained to recognize and neutralize a familiar specific antigen; its immune system "remembers" the antigen. Such systemic (not restricted to the initial infection site) immunity enables a faster, longer lasting immune response than does a nonspecific response.

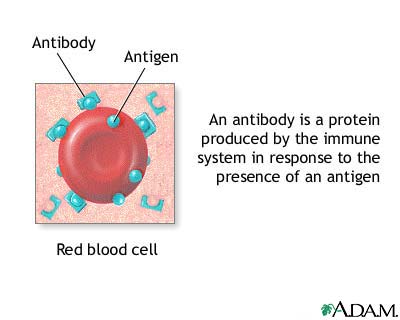

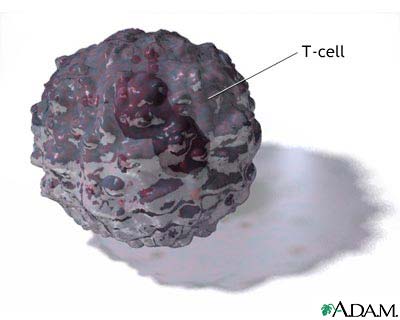

Lymphoid tissue and bone marrow: immune cell production Lymphoid tissue and bone marrow form the immune system anatomical core. The thymus gland is the primary lymphoid organ for lymphocyte development. The red bone marrow produces B-lymphocytes (B cells) and T lymphocytes (T cells). B cells achieve immunocompetence (ability to recognize a specific antigen) in bone marrow. T cells migrate to the thymus gland, where they become immunocompetent. However, the lymphocytes are immature (not fully developed) and cannot directly participate in an immune response. Immature B cells and T cells migrate from their primary lymphoid sites (bone marrow and thymus) through the vascular and lymphatic systems to secondary lymphoid sites. These sites include the spleen, lymph nodes, tonsils, and Peyer's patches in the intestine and appendix. These immature B cells and T cells immature only after they meet an antigen. B cells abound in lymph nodes, the spleen, lymph nodules, and the blood. B cells produce antibodies that destroy specific foreign antigens. Antibodies circulate in the humours (body fluids), creating humoral immunity, a type of specific immunity. The three types of T cells are killer (cytotoxic), helper, and suppressor T cells. All destroy antigens. T cells mature in the thymus. They do not produce antibodies; instead, they attack the antigens directly, providing cell-mediated immunity, another type of specific immunity.

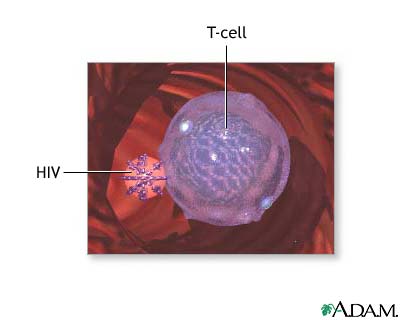

In an autoimmune response, lymphocytes are unleashed against the body cells. One autoimmune response example is rheumatoid arthritis, in which immune system cells release chemicals that adversely affect joints of the fingers, wrists, ankles, and feet. The result is chronically inflamed joints that become more painful and less mobile as the autoimmune response continues. AIDS Sometimes, cell-mediated immunity is weakened and the body becomes prone to life-threatening infections that might not otherwise be so. This condition occurs in AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome). The human immune-deficiency virus (HIV) causes AIDS. The HIV virus attacks and kills helper T cells (specialized T cells that "direct" the immune response). The immune system is severely depressed and its ability to resist infection impaired.

|

Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited. The information provided herein should not be used for diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition and is provided for your general information only.